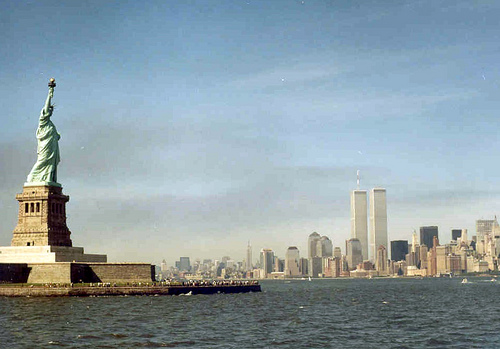

September 11, 2001

I grew up in the New York City enclave of Fairfield County Connecticut. On September 11, 2001, I was a junior in high school. More than half of my friends and classmates had parents who worked in or near the World Trade Center.

It isn’t hard to imagine what happened after the Principal announced over the loudspeaker that despite learning of terrorist attacks in New York, we should go about our day as normal: chaos ensued.

I immediately tried to contact my mom on my cell phone to no avail. In fact, I remember the exact words of the pre-record message I heard over and over as I pushed redial: “all circuits are busy. Please try your call again later. This is a recording. Two oh three, one two oh.”

It was the same story for virtually all of my peers. The phone lines were jammed throughout the day and the only option for many was to wait at the commuter train station for hours, praying for loved ones to arrive on the next train.

At the same time, town officials were scrambling to provide the public with information. Hundreds of residents tried to contact local law enforcement to report missing persons and to ask for instructions on what to do next. My parents, both police officers in our town of about 18,000, were part of a coordinated response, but because citizens were having trouble connecting with emergency responders, it was a long and frustrating process. There was simply no way to quickly and efficiently disseminate information to citizens.

August 23, 2011

Fast forward to August 23, 2011. I was in my apartment in Northwest Washington DC and felt the earth shake beneath my feet. Aside from the two pictures that fell off the wall, I was fine. But I didn’t have any idea what was happening. Was it a terrorist attack? A really large dump truck? Were my friends and family okay? Just as it had been ten years earlier, my first instinct was to make a call using my cell phone. Again, the phone lines were jammed. So, I logged on to popular social media sites.

I learned through tweets posted by both official and unofficial sources that I had just experienced my first earthquake. I turned to Facebook to post the message that I was okay, and then scrolled through my newsfeed until I was certain that pretty much everyone I knew was safe as well. Ten minutes after the earthquake I knew what was going on, had connected with friends and family, and headed downstairs to the local watering hole to enjoy a cocktail and watch the news.

Then and Now

The aftermath of the September 11th attacks was much different from that of the earthquake. Still, for me the first few moments of both felt very similar: the panic, the fear, and the sense of urgency to connect to loved ones.

On September 11th I did not have an easy way to connect and there was just no easing that initial wave of panic. When confronted with a possible disaster situation ten years later I was quickly calmed by the information I obtained and disseminated via Facebook and Twitter.

There’s no denying the value of social media when it comes to quickly and efficiently sharing and gathering information in the first few minutes of a crisis. There’s also no denying the complications that arise. But that’s a different story.