This week in our “Twit Happens” tweet regret blog series we’ll discuss what happens when emergency management personnel and government communicators make the mistake of not participating in the social media conversation. In times of crisis, when agencies should be leading the conversation and providing reliable information, a failure to communicate leaves concerned citizens at the mercy of rumor mills and fear mongers.

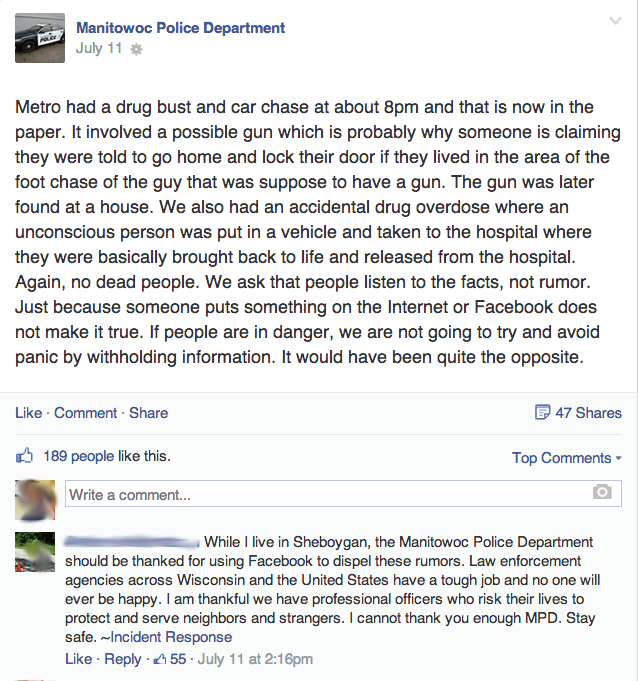

First, an example of how to do it right. The police department in Manitowoc, Wisconsin demonstrated social media best practices last week when they used Facebook to provide accurate information to squash rumors about a man with a gun.

Note the next to last line of the post,

“If people are in danger, we are not going to try and avoid panic by withholding information.”

If only all emergency management and law enforcement agencies understood this, we could avoid a great deal of panic and worry. The commenter even thanks the Manitowoc PD for using Facebook to dispel rumors.

US House of Representatives Sets a Precedent

Fortunately, the federal government is setting a precedent for other agencies to follow. Last week the US House of Representatives passed the Social Media Working Group Act of 2014 — a bill designed to amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to include social media strategy for communicating with the public in the event of a terrorist attack. As the bill’s sponsor Rep. Susan W. Brooks says, “social media has dramatically changed the way we communicate with each other and using it the right way can save lives when disaster strikes.”

Failure to Communicate: What might go wrong

For an example of what can happen when an agency fails to communicate crucial information in a timely manner, let’s look back at the swine flu outbreak in 2009. When the outbreak began, rumors started flying on Twitter regarding germ warfare and contaminated meat. Instead of stepping in to squash these rumors as the Manitowoc PD did, government health organizations stayed quiet as the misinformation continued to spread.

The Consequences

To some extent, this led to increased caution and concern from agencies already nervous about joining social media, yet organizations such as the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO) were criticized for not doing enough to combat the spread of misinformation. The rumors spreading across social networks created unnecessary panic within the general public. In other words, the CDC’s hesitancy to participate in the social media conversation proved more risky than actual involvement. While they did post status updates, they stayed out of the larger conversation to deleterious effect.

How to Recover

Unfortunately, by the time a failure to communicate becomes obvious, it might be too late to recover. Regardless, the situation can be evaluated to best understand how to avoid communication gaps in the future.

During the swine flu outbreak, health organizations should have been at the forefront of the social media conversation. Statements should have been released promptly at the start of the epidemic, and continually updated with the latest developments. To their credit, the CDC was issuing official status updates and action plans regarding the disease. However, the public may have been better served if the CDC and others had taken a more proactive approach by replying to tweets and discrediting false information.

If a high profile situation such as this has shaken public confidence in your organization, it is worthwhile to perform a retrospective and create an action plan for the future. In fact, using social media to share your action plan is a good way to reinforce your commitment to communicating more effectively. We’ll see if the Homeland Security Agency takes this approach to promote their plan if the Brooks Bill passes in the Senate and becomes law.

Emergency Management Communication Done Right

For an excellent example of how Twitter can be used to communicate and coordinate in the event of a natural disaster, check out how Bronlea Mishler, the Deputy Director of Snohomish County leveraged social media during the March 22 mudslide in Oso, WA. Bronlea’s story provides an excellent case study on how Twitter and other social media networks can assist with emergency management. The representatives behind the Brooks Bill should give her a call.

Next week on Twit Happens: Tweet Regret

Next week we will cover a topic that keeps IT Directors up at night — getting hacked. We will examine a case of Twitter hacking and offer tips for recovery and for preventing future attacks.

All five installments of the Tweet Regret series are available now when you download our complimentary eBook: Twit Happens – Tweet Regret in the Public Sector. Get your copy today!